Roselle Knott by Stan Nowak

This article was first published in the Dundas Star News, September, 2004. Reproduced with permission of the author.

The play was going well, and the audience was enjoying it. The smoky stage was particularly effective—except that it wasn’t part of the play. Smoke was billowing from behind the stage, but the leading lady assured the audience that all was under control and continued with her performance. Although the theatre was filling with smoke, hardly anyone left, and by play’s end, the fire was doused. The next day in Logansport, Indiana, the play “Alice Sit-by-the-Fire”, received great acclaim, as did the star, Roselle Knott, whose coolness had averted panic during a potentially perilous situation.

The play was going well, and the audience was enjoying it. The smoky stage was particularly effective—except that it wasn’t part of the play. Smoke was billowing from behind the stage, but the leading lady assured the audience that all was under control and continued with her performance. Although the theatre was filling with smoke, hardly anyone left, and by play’s end, the fire was doused. The next day in Logansport, Indiana, the play “Alice Sit-by-the-Fire”, received great acclaim, as did the star, Roselle Knott, whose coolness had averted panic during a potentially perilous situation.

Roselle Knott was born Agnes Roselle (some sources say Victoria Roszel) in Dundas on March 19, 1865 and began her theatrical career with the amateur Dundas Dramatic Club. In 1884, she married Edward Knott, a fellow actor of considerable repute, and together they played to marked success for twelve years until January 1896, when Edward would die tragically as the result of a lacrosse accident. They had three children together: Ivey, who died in infancy in 1885, daughter Viola, who also became an actress, and a son Thomas.

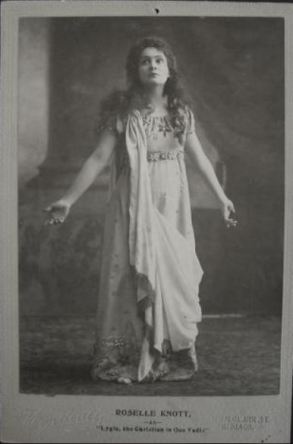

Roselle made her professio nal debut in 1887 in the old Hamilton Academy of Music. As a leading lady, she earned unstinted praise for her performance in Steele McKay’s “Paul Kauver”, and later as “The Empress Josephine”. But greater acclaim awaited her south of the border. In 1893, she made her New York debut playing in “As You Like It”, but became the toast of the town later that same in year in “Quo Vadis”, where she played Lydia for three years running in the Empire Theater. Successful tours later followed in Chicago and Boston.

nal debut in 1887 in the old Hamilton Academy of Music. As a leading lady, she earned unstinted praise for her performance in Steele McKay’s “Paul Kauver”, and later as “The Empress Josephine”. But greater acclaim awaited her south of the border. In 1893, she made her New York debut playing in “As You Like It”, but became the toast of the town later that same in year in “Quo Vadis”, where she played Lydia for three years running in the Empire Theater. Successful tours later followed in Chicago and Boston.

Roselle joined the Mansfield Company and starred in leading roles in “Parisian Romance” and “Beau Brummel“and became the highest-paid stage performer of the time. But it was in 1902–03 as Mary Tudor in “When Knighthood Was In Flower” that she won her greatest fame. The author, Charles Major, later said to her, “You stepped right out of my book”.

Roselle returned in 1904, to live in Hamilton and on June 28, 1905, she saved herself and her manager from a near-drowning in the Hamilton Bay ‘by her presence of mind and rare coolness’. In March 1906, she played the real-life heroine once again during that theatre fire in Logansport.

Ill health forced her into retirement from the stage in 1907. It was also around this time that Roselle married promoter Ernest Shipman, with whose company she had worked. By the time they finally divorced in 1912, there was no love lost between the two. Later, both their obituaries never acknowledged one being wed to the other.

By 1911, a healthy Roselle had returned to the stage playing Portia in “The Merchant of Venice” with Robert Mantell’s company. She also played Lady Macbeth, Katherine in “The Taming of The Shrew”, Juliet and many other great Shakespearean roles.

By 1911, a healthy Roselle had returned to the stage playing Portia in “The Merchant of Venice” with Robert Mantell’s company. She also played Lady Macbeth, Katherine in “The Taming of The Shrew”, Juliet and many other great Shakespearean roles.

In 1915, Roselle returned to Hamilton and directed plays for the Imperial Order of Daughters of the Empire, of which she was a lifetime member, but in 1916, she moved to New York City, founding a very successful theatre company which toured major cities of the United States.

Roselle retired from acting in 1936 and opened an acting studio in New York to tutor promising young talents. Her studio produced such stars like Robert Montgomery and Miriam Hopkins. But a year later, another serious illness forced her to close up shop, and she moved back to Hamilton. In 1945, Roselle suffered an illness from which she never fully recovered, and she died early in 1948.

For almost fifty years, this lady from Dundas thrilled North American audiences from the 1880s well into the 20th century. Her passionate dramatic performances assured her status as a bright light during the golden age of live theatre. Stan Nowak

Darkness befalls Dundas at Noon

by Stan Nowak

This article was first published in the May 13, 2005 edition of the Dundas Star News. Reproduced with the permission of the author.

The unrepentant heat wave offered perfect conditions for the fire to spread throughout the thirsty fields of the northern Alberta  plains. The air blackened as the smoke churned upwards into the sky, while the inferno dominated the horizon and swelled, igniting the arid grasses in its path. The flames were everywhere! It was only just beginning.

plains. The air blackened as the smoke churned upwards into the sky, while the inferno dominated the horizon and swelled, igniting the arid grasses in its path. The flames were everywhere! It was only just beginning.

The day began as a typical autumn Sunday in the Valley Town. Family calendars were filled with the customary Sunday services and the usual family meals and gatherings. But by late morning, the promising sunny day started to change as unfamiliar dark clouds of red and copper rolled in from the west. Further to the west, an approaching solid black cloud seemed to forecast a storm of epic magnitude.

By noon, the town was blanketed by a “spectacular yellow haze” that just grew darker as the day went on. Lawns took on a softer hue of green as the smoke filtered the sunlight blocking out blues and violets. Dogs howled, horses and cows were agitated. Even the birds were a little bewildered as they all ceased their singing and chirping and were seen nervously huddled in their nests or in eavetroughs. By mid-afternoon, as the unearthly darkness continued to descend, cars needed to turn on their headlights to drive through town. The streets were deserted except for youngsters perhaps hurrying home a little faster than usual from their Sunday School classes.

day went on. Lawns took on a softer hue of green as the smoke filtered the sunlight blocking out blues and violets. Dogs howled, horses and cows were agitated. Even the birds were a little bewildered as they all ceased their singing and chirping and were seen nervously huddled in their nests or in eavetroughs. By mid-afternoon, as the unearthly darkness continued to descend, cars needed to turn on their headlights to drive through town. The streets were deserted except for youngsters perhaps hurrying home a little faster than usual from their Sunday School classes.

Above the town, the sky was aglow with various shades of yellow, grey, and pink. At times, it seemed like the sun was shining from true north. Periodically, the solar disc itself would appear through the filtering smog, but with no apparent glare. The Desjardins Canal turning basin offered a fantastic reflection of the bruised clouds and dramatic visions overhead.

As the prairie fires intensified, with the black smoke providing an eerie backdrop to the brilliantly coloured flames, prevailing winds from the west began to shift the expanding cloud eastward. Soon, half the continent—including the Town of Dundas, Ontario—was blanketed in abnormal darkness.

The sky was still overcast late in the afternoon when the lights went out, and Dundas was plunged further into darkness. This electrical power failure happened as the result of an energy transfer from the John Street to the King Street electrical station as part of a routine maintenance procedure. A planned shut-down had occurred earlier that day, but full power was restored by 9:30 A.M. This second power outage was to be a brief one. But the smoggy situation taxed both stations as residential electrical demands increased for their lights and furnaces (the temperature plummeted by 8 degrees F). Thus, by 5:30 P.M., when the energy transfer had been completed to the King Street station, it was too much for the station to handle, and an extended power failure occurred.

Dundas residences were ablaze in candlelight as Sunday dinners were eaten in true pioneer style that night. Sunday night church services that evening were larger than normal. The people of Dundas must have felt that the biblical apocalypse was nigh as that Sun day, the 24th of September 1950 came to a somewhat uncertain conclusion.

day, the 24th of September 1950 came to a somewhat uncertain conclusion.

Monday morning of the 25th saw the end of the drought as overnight rains fell on Alberta, which helped quell the 36 separate fires, including a fifty-square-mile blaze some 340 miles north of Edmonton. The outside temperature fell to comfortable levels and the crisis was over.

That Monday morning also saw Dundas, Ontario restored with full electrical power as a typical work week commenced. Though traces of the smog were still evident, they were expected to dissipate in time for the total lunar eclipse expected that night. Otherwise, the day was seasonably warm, and the sky overhead was sunny and blue. The End